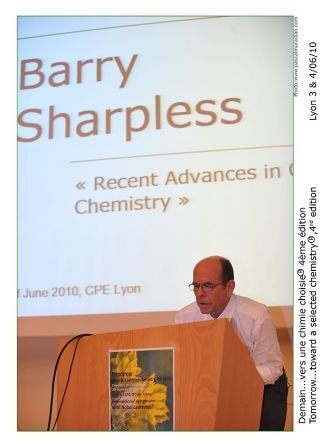

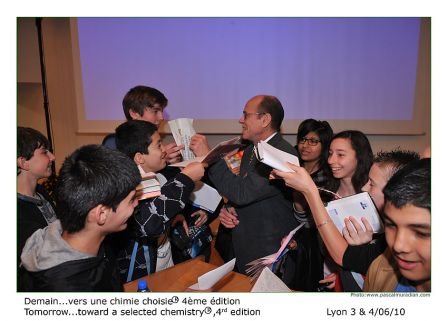

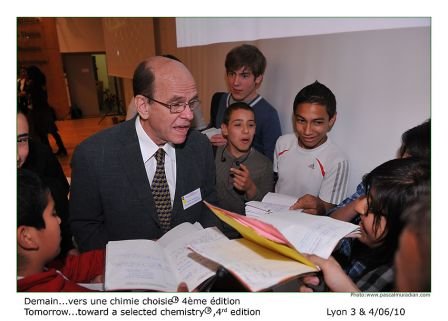

I was so proud to welcome Barry Sharpless to Lyon, 3&4 June during the symposium "Tomorrow... towards a selected chemistry". He spent several hours to answer questions from young students with such passion and enthusiasm! Thank you Barry.

SEARCHING FOR NEW REACTIVITY* Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2001 by K. BARRY SHARPLESS The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Rd, La Jolla, CA 02037, USA. In 1938, three years before I was born, a live coelacanth was taken from the waters off the eastern coast of South Africa. Previously known only in the fossil record from some hundred million years ago, the coelacanth and the implications of its discovery remained big news for years, fueling an enthusiasm for “creatures” that persisted for decades. Those of us born in the Forties grew up on photos of eminent scientists setting off on expeditions, their sunburnt faces dwarfed by mountain explorer’s garb, or making thumbs-up signs as they entered the water in scuba gear. We shared their confident expectation that the Loch Ness Monster, Sasquatch, the Yeti – even a dinosaur – soon would be taken alive. I grew up loving the sea and loving fishing in particular, but unlike most fishermen I cared less for the size or quantity of the catch than for its rarity. Nothing could be more exciting than pulling (if not this time, surely the next!) a mysterious and hitherto unknown creature from the water. As a kid, I passionately wanted to be one who caught the next coelacanth, the first to see something that was beyond reasoning, even beyond imagining. Opening a Nobel Lecture with a fishing expedition may seem frivolous, even indecorous, but I assure you no disrespect is intended. These are the circumstances that shaped my professional life: my first laboratory was New Jersey’s Manasquan River, whose astonishingly rich variety addicted me to discovery; a few years later, when I was as comfortable at sea as I’d been on the river, my laboratory became the Atlantic Ocean; later when I started doing chemistry, I did it the way I fished – for the excitement, the discovery, the adventure, for going after the most elusive catch imaginable in uncharted seas. Chemists usually write about their chemical careers in terms of the different areas and the discrete projects in those areas on which they have worked. Essentially all my chemical investigations, however, are in only one area, and I tend to view my research not with respect to projects, but with respect to where I’ve been driven by two passions which I acquired in graduate school: I am passionate about the Periodic Table (and selenium, titanium and osmium are absolutely thrilling), and I am passionate about catalysis.

- Adapted with the permission of the editors from “Coelacanth and Catalysis”: K. B. Sharpless,

Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 4235. What the ocean was to the child, the Periodic Table is to the chemist; new catalytic reactivity is, of course, my personal coelacanth. Even though I grew up in Philadelphia, if someone asks me where I’m from, I usually say “the Jersey Shore,” because that’s where my family spent summers, as well as many weekends and holidays, with my father joining us whenever he could. My father had a flourishing one-man general surgery practice which meant he was perpetually on call. With him at home so little and practically guaranteed to be called away when he was, my mother liked being near family and friends at the Shore, where her parents had settled and established a fishery after emigrating from Norway. When I was a baby, my parents bought land on a bluff overlooking the Manasquan River about four miles up from where it enters the Atlantic. Like many scientists I was a very shy child, happier and more confident on my own, and my interest was totally absorbed by the river. In those days, the incoming tide transformed our part of the river from a channel flanked by broad mud flats to a quarter-mile basin that exploded with life of myriad variety – about a dozen kinds of fish big enough to make it to the dinner table, plus blue crab, eel, and a bounty of fry and fingerlings that would graduate downstream to the ocean. I was obsessed with finding and observing everything that lived in the river and knowing everyone who worked on it. My most delicious childhood memory is the excitement I experienced at the instant of awakening almost every summer morning. The sound I associate with that feeling is the distant whine of my first scientific mentor’s outboard motor. That was my wake-up call, and within minutes I was at river’s edge, waiting in the pre-dawn stillness for Elmer Havens and his father Ollie to make their way across the river from Herbertsville to pick me up to “help” them seine for crabs. Amused by my regularly walking along the bank to watch them haul their seine, Elmer eventually installed me in the boat, which he used for transportation as well as for steadying himself as he dragged the seine’s deep-water end. Ollie walked one end of the seine along the shore, alarming the crabs gathered at the river’s edge, and frightening them toward deeper water and so into the net’s pocket. Chest deep in water and mud, Elmer walked parallel to his father, one arm clasping the seine, the other hooked over the boat’s gunwale. Elmer and I, our heads close together, would speculate about the catch, taking into account all the variables – the weather, the season, the tide. Every hundred yards or so, Elmer doubled ahead toward the shore to draw the purse. I liked it best if a big eel or a snapping turtle got caught up in the net, making the water boil and the net flop into the air. I always hoped we’d catch something new. I had a little dinghy, and my realm of exploration expanded in direct proportion to my rowing ability. But the same tide that created this abundant estuary also was my nemesis, forever stranding me upriver in the narrows or perhaps at Chapman’s Boat Yard, a mile downstream and on the opposite bank. Since my parents couldn’t keep me off the water, they opted for increasing the likelihood of my getting home unaided by giving me a boat with an outboard. It wasn’t long before I went down river all the way to the inlet 226 227 (absolutely forbidden, of course), and, soon after, the prospect of new creatures to pull from the water lured me out through the rock jetty and into the ocean; at the time I was only seven or perhaps eight years old. By the time I was ten, I ran crab and eel traps and supplied everyone we knew with fish as well; at fourteen I started working during the summer as the first (and only) mate on a charter boat. My parents allowed me to go to sea when I was so young and small even for my age because I was offered a job on a relative’s boat – little did my parents or I know that Uncle Dink, a cousin actually, offered me the job so he wouldn’t have to pay a “full-sized” helper. I so wanted to keep working on the boats that it was years before I dared tell my parents what went on aboard the Teepee, like how the Coast Guard refused assistance to Dink because his boat was in chronic disrepair. (Consequently, some of our adventures at sea were memorable indeed – grappling hooks and guns have their place in the canon – and I mention this trove of Uncle Dink stories because for years my MIT colleagues begged me to tell them over and over again.) On a charter boat the captain pilots the ship and finds the fish the customers reel in. Meanwhile, the mate is over the boat like a dervish, skillfully arraying the water with fishly temptations – adjusting outriggers, finding the perfect combination of lure or bait and tackle, always mindful of the action on nearby boats competing for the same fish.* Since my friends were all mates we naturally agreed that enticing fish to bite was the greatest challenge, but I alone felt that getting the strike was the most fun, even more exciting than landing the fish. I worked as a mate almost daily every summer, right up until the day before I set out from New Jersey headed toward the biggest ocean and graduate school at Stanford University. That was in 1963. In the spring of that year my inspiring Dartmouth College chemistry professor and first research director, Tom Spencer, talked me into delaying entering medical school to try a year of graduate school. He sent me to Stanford specifically to work for E. E. van Tamelen, Tom’s own mentor at Wisconsin. The appeal of fishing was such that Tom, to my later regret, never succeeded in getting me to spend any summers working in his lab. In fact even in graduate school I expressed my ambivalence by continuing to fantasize about finding a boat out of Manasquan to skipper and by failing –

- This diversion into fishing-as-metaphor-for-research could go on for pages: consider how when

a boat was hooking tuna – the catch of choice – word spread by radio and the competition converged from every compass point. The hot boat’s captain greeted this acknowledgment of his success with some anxiety: while he liked setting the other captains’ agendas and pleasurably speculating that the parties on the other boats were considering chartering him next time, the secrets of his success nonetheless required protection, so trolling speeds were lowered to sink the lures and prevent rubberneckers from identifying them, and red herrings (literally, on occasion!) were casually displayed on the fish box. Isaak Walton and John Hersey devoted whole books to this metaphor, so indulge me for a few more sentences. The handy process vs. product dichotomy that applies so neatly to much of human endeavor illuminates this fisherman-chemist comparison, too. Conventional wisdom places fly-fishing at the “process” end of the scale, while a “product” fisherman uses sonar to find a school before he bothers to get his line wet. Process person though I am, only the Manasquan River ran through my fishing days: trolling for the unknown always had more appeal than hooking a trout I already knew was there. 228 this did not please v.T. – to do the simple paperwork required to renew my NSF predoctoral fellowship. However, toward the end of my first year at Stanford, a serendipitous misunderstanding catalyzed the complete transfer of my passion (some would say my monomania) from one great science to another, from fishing to chemistry.